as expressed in their works on social progression in the post-independent Singapore

‘The sparrow though small has all five organs’, goes a Chinese adage and nothing could be truer than this for Tamil writing in Singapore. Long before Tamil writing arrives at today’s postmodern landscape, creative migrant voices could be heard from Singapore.

Over a century, Singapore has to its credit many firsts in the Tamil literary sphere. First poetry collection of the region in Tamil, Munajattut tirattu was printed at J. Paton Government Printer, in Singapore in 1872. [1] Singai Vartamani, first Tamil newspaper of the Malay Peninsula appeared in Singapore in 1875. [2] First anthology of Tamil short stories Navarasa Katha Manjari, was published from Singapore in 1930.[3] Singapore has the credit as the first in the world to launch on the internet the Poemnet, an anthology of poems in all four national languages of Singapore. H E Mr Ong Teng Cheong, then the President of Singapore, launched the anthology, Journey: Words, Home and Nation -Anthology of Singapore Poetry (1984-1995) in the Poemnet, in October 1995. [4]

But the pride of any literature does not rest on just being a pioneer, but on being alive to social realities. Since Kudirai Pandhya Lavani (1893), a folk-styled poem on horse racing in Singapore that describes the street scenes lively, Tamil writing in Singapore is buzzing with the portrayal of social actualities.With Singapore becoming a country and was in making of a modern nation in mid-sixties, Singapore literati became sensitive to new realities

Being minority among the four races in Singapore and a majority among the Indian community, Tamils enjoy a paradoxical position, but it hardly spills over into their writing. Yet, Journey of Tamil writing in Singapore is like travelling in a moving train, in a broad daylight, presenting you with a variety of landscapes, people and their postures (and unlike wandering in MRTs that surge through underground tunnels).It chugged off slowly after an initial dilemma but soon found its way in the seventies, settled with its pace in eighties and picked a swift momentum from 90s.

Considering the enormity of the subject, I have restricted my study to the fiction and poetry (which form a big chunk of Singapore Tamil literature) written /published between 1965 and 2015.Illustraions in this paper are from the works of writers who have won coveted literary awards either in Singapore or abroad.

Transformation

Unlike many countries in Asia that fought bitterly, bloody in some cases, with their colonial rulers for their independence, Singapore became Republic at an unexpected moment of history, like a ‘bolt from blue’ [5] on August 9, 1965. Shocked, but undeterred, the founding fathers of modern Singapore, saw an opportunity in the crisis, an opportunity to build their dream nation state, a multi-racial, multi- lingual, multi-religious, tolerant society. But the challenges ahead were not merely cultural. There were pressing ‘bread and butter’ issues — stabilising economy with no natural resources except a deep seaport and no hinterland, sustaining development, creating jobs, building new habitats, ensuring education for all, and defending the new found sovereignty from colonialism and communism demanding priority. The founding team, “English educated colonial bourgeoisie” as Mr.Lee Kuan Yew would describe [6], got into action investing their vision and commitment coupled with their intelligence and hard work.

Their determined work brought in many changes in the lives of many Singaporeans and Singaporean Tamils are no exception. “Three major initiatives that transformed the lives of Tamils lives,” according to Dr.A.Veeramani, are “housing, education, and the rapid pace of economic growth” [7] I would list the following are some of the major milestones of transformation:

- Becoming the Independent Republic

- Kampongs to HDB

- National Service

- Education Policy

- Status of Women

- Economic Prosperity

- Economic Slowdown

- SARS

Becoming the Independent Republic

As said earlier, when the new Singapore Republic was born, there was no fanfare, fireworks, frolic or feasts. It was a moment of anguish and uncertainty. The country still remembers, the legendary press conference wherein Mr.Lee Kuan Yew, a person of strong will and resolute, tearfully explained the reality of independence before the television cameras. Like all others Tamil community too was stunned and scared [8]. Tamil newspapers seemed to have believed that the separation from the federation was a miscommunication between brothers and would be resolved in course of time. They were hoping against the hope that Singapore would rejoin Malaysia. [9]

But reality dawned on them soon. After a brief silence, poets filled the air with their poems in praise of Singapore and its leadership. K.Perumal came out with a poetry collection, ‘Singapore Padalkal’ (Hymns on Singapore) [10.] This collection, with 133 songs of him, is entirely on Singapore as a nation. Mr.V.T.Arasu, in his preface to the book, hails the work: “Out and out all the songs are on Singapore Yet the poet has not drowned the songs on the description of the landscape and in exaggeration. On the contrary, he points out the basic values of Singapore” [11]

Paranan, a SEA Write awardee (1986) has devoted 19 poems (out of 100) in his collection Thoni (Boat) to sing in praise of the Republic. [12]

Nudged by media National day came in handy for poets as an occasion to display their pride and patriotism

On the 10th anniversary of Singapore becoming a Republic, Na.Palanivelu, recipient of Cultural Medallion (1986) eulogised in his poem ‘duty’:

Ten tears of independent rule

Has made us undeniably world renowned

Small pearl like clusters of islands fronting it

Our Singapore emerges like a diamond radiating in all directions

Telling for the splendour and affluence of the land

Let us put our earnest resolve to prosper further

This is our duty [13]

Naa.Aandeappan matches Palanivelu metaphorically in his poem Uyarthara Vairam (“classy diamond”) when he says

Singapore floats like a classy diamond

In the saline sea [14]

A similar portrayal is reflected in Pichinikkadu Elango’s poem August 9 where he symbolises “Singapore as golden plate floating in deep sea” [15]

Over the period of time, these poetic outflows turned to be a ritualistic exercise rather than exuberant expressions as it became a routine.

Kampongs to HDB

Post republic, when Singapore underwent rapid urbanisation, many kampongs, maybe a few hundred, transformed into high rise apartments. On the first sight, these HDB apartments stand as visible testimony to the awe-inspiring Singapore’s story of development.

HDB is undoubtedly a masterstroke in making Singapore into a modern metropolis. By 1962, in just two years, HDB had built 26,168 units, approximately the same number of units built by Singapore Improvement Trust in 32 years. And by the end of 1965, its tally exceeded 50,000 units.[14] In less than a decade, in 9 years to be precise, 1.5 lakh people were relocated.[17]

This one step has changed dramatically the lifestyle of many Singaporeans of the earlier generation. Moving from rickety wooden houses with attap roofs and without electricity to concrete blocks with tiled floors is not just a migration but a journey: A journey from primordial past to promising future; a journey from aggravation to advantage; a move from misery to modernity.

C. Kumarasami, a veteran Tamil activist, describes the misery in his article, “Life in Pasir Panjang“: Crowded in a small space, people lived in huts in kampongs. Most of the huts were a single room accommodation and in many of them, there were no kitchens. One has to cook, eat and sleep in that small room. And there were no cots to sleep. Every family had four or five children. Like seeds arranged in a beans pod, all of them will sleep next to each other. Yet efforts for procreating another child was also initiated in that milieu” [18]

However for many HDB residents relocation caused distress. Some were afraid of lifts and constantly climbed stairs. All residents had to adjust overnight to new neighbours of different races. Those accustomed to living close to the ground with livestock and poultry found relocation to HDB challenging. The metamorphosis from kampongs to high rise buildings is oscillating like a pendulum in grandfather’s clock, between a romantic past and an inevitable reality.

Mayandiambalam Balakrishnan, more popularly known by his pen name, Singai. Ma. Elangkannan, first Tamil writer to receive the South East Asian Writers Award in 1982, portrays a poignant picture of parting cattle raised at a Kampong home in his novel Ninaivukalin Kolangal (“designs of memories”):

“Those standing in the truck pulled the cow by the rope in its nose. Refusing to walk in the cow pulled them back. A person standing behind the cow twisted its tail to nudge it forward. The cow, still resisting, plodded into the truck. It shivered in fear and shat. Thrusting its neck forward, it cried, helplessly “..Moo!” Tears appeared in the eyes of Maragatham, who was watching its plight. It appeared to her as if the cow is crying Amma (mother) towards her. She turned aside. And there stood the cow with black spotted skin. It has become barren now. Her husband, Murugaiya, used to say more often, “We became better off with her. Let us not sell it. Let she die here” Her husband’s word passed through her mind. Tears rolled down her cheeks. Unable to bear the sight she rushed in.” [19]

It is not just the cattle they missed when they moved to high-rise flats, but their kinship with their neighbours in the kampongs Unlike Elangkannan, Kanagalatha, who writes under the pseudo name Latha, is a writer of another generation and was not a witness to the transformation of the 70s. Yet she presents the anguish of the loss of comradeship in the relocation through one of her characters in a short fiction, Veedu (“home”) “We were moving with each other like sisters, but the relocation threw us apart to different directions. Having accustomed to a living close to the ground and next to trees, I found high rise living challenging. It was living as if confined to four walls and was suffocating. I couldn’t sleep and it took a long time for me to adjust to the new surroundings” [20]

But these agonies, on the other side of the coin, had its own ecstasies. Ilangkannan didn’t fail to depict the excitement on arriving at the new flat:” Getting down from the Taxi Velu and Ezhilarsi, looked up at the high rise building. ‘Do you see a sari drying on the cloth line? At the 10th floor? .That is our house. Maragatham also got a flat close to us” said Muthammal, walking towards the elevator. The flat looked nice. Floors were paved with tiles. The kitchen looked clean and neat. Peeping into the kitchen, Velu expressed his surprise: “Is this our kitchen?” [21]

Like Velu, many of our Tamil poets were excited about these skyscrapers. For poets, the romantic façade of the high-rise apartments had eclipsed the pangs of relocation. N.Palanivelu, recipient of Cultural Medallion, in his poems claims the miseries have vanished like a dream [22]. K.T.M. Iqbal, an eminent poet and recipient of SEA Write Award and the Medallion, is fascinated with the cloud-kissing-skyscrapers[23]. Paranan, another veteran, goes further up and awestruck with the tall residential flats that block the sun! [24]

However dramatic the romantic side is, the bottom line of the high-rise living was the budgetary pressures it excreted on the purse. In a radio drama series, Aduku Veetu Annasami,(Annasami and his apartment) that was on the broadcast for 52 weeks, Pudumaithasan (P.Krishnan) another awardee of Cultural Medallion, brings out the pinch on the valet.

Santhammal: Did you notice how much comfortable this house is? There is a hall, a bathroom and kitchen. We lived in a kampong. You were so adamant to stay there. But, now look at this place.Nice, isn’t it?

Arockiasamy: What was the rent you were paying there? Do you remember? It was 15 dollars. And the rent here? 46.5 dollars. If you add water and electricity charges, it would easily exceed 55 dollars.

Santhammal: This being a HDB flat the rent is limited to 46.5 dollars. Go and check what the rent would have been, had this been a private flat; then rent would have been 80 or 100 dollars.

Arockiasami: Should comfort cost that much? Can’t that be made available for 15 dollars? [25]

But the best comfort one can aspire for in life is the freedom from fear. To much of our dislike, kampongs were once infested with thugs. As tenants had some protection under the rent control legislation, landlords in various parts of Singapore hired the ‘services’ of the gangsters. They, the gangsters, used to threaten the residents, start fires here and there in the kampong to evict them. Pathmanaban Selvadurai, former Member of Parliament, narrates an experience in Bukit Panjang: from kampong to town: ” I had a representative from this company – he saw me in my branch and said: ” We will help you in getting rid of the Barisan Sosialis (an opposition political party) because all these squatters were Barisan Sosialis supporters. If (we support them) they (would) send in their gangsters and employ strong-arm tactics. I had to tell them: “Well, look, thank you very much, we are a government party, we can’t indulge in that kind of activities. But if you give these fellows a fair deal in terms of compensation, I will assist you, fellows, to get (the squatters) out.” [26]

Noorjahan Sulaiman, in her novel, Vergal (“Roots”) makes a mention about the thugs in the kampong:” In those days there were gangsters in kampongs, almost in every street” [27]

Accounts of kampong life transcend beyond the triumphs and travails of modernisation as they bring to us the human side of urbanisation. After all, that is what literature strives for centuries. Today kampong life has no relevance than being a reminder of the past when life was simpler rather than easier.

National Service:

Being a small country in terms of population is bliss in many ways but it may also turn to be a disadvantage at times. When Singapore became independent it had an army that was grossly understrength and with vintage weapons. Initially, a part -time reservist force, People’s Defence Force, with 3200 part-time volunteers was formed. Dr.Goh Keng Swee, Minister for interior and defence, realised with Singapore’s population at less than two million it would have been impossible to form and maintain a large army like those of Singapore’s neighbours[28]. He proposed a citizens’ army and thus born the National Service in July 1967.

National Service had two facets that are sentimental: A sad one, as one has to be away from the family for a while. As Mr Lee says, “Soldiers and uniforms of any type used to have unhappy memories for us” [29] And the proud one: As expressed by S.Rajaratnam: ““ When young Chinese, Malays, Indians, and Eurasians train together to defend and die for their country, then they become true blood brothers.” [30]

Irama. Kannapiran, a SEA Write Award winner (1990) brings out both the facets effectively in his story Tanah Merah Diary [31]

“Amot, the drill master, a man with a benevolence concealed under the guise of strict disciplinarian touches our heart, relegating the main characters to the background, in Tanah Merah Diary. If a character, which is minor and appears for a fraction of a second in a story could move us, then it stands an evidence for the skill of the author” wrote Se.Ve.Shanmugam, a contemporary writer of Kannapiran, while commenting on the story [32]

Education Policies:

- Bilingualism

British under their colonial rule had allowed Singapore’s different ethnic communities, to educate their own children in their own mother tongue. Children of different races were taught in their own languages. Economic necessities of newborn Singapore demanded an approach that is far different from the British approach. Leaders of Singapore saw the English held the potential to build its economic future and to be a link language between the ethnic groups. A Singaporean bilingualism model was created with a dominant place for English, as the medium of instruction at all levels and the mother tongue as the second language.

Tamil schools in Singapore have a unique history. Most of them were founded by working class and through public contribution [33].

When the new bilingual policy came into force they vanished one by one, as sensing the better career opportunities with English medium education, many parents in Tamil community, shifted their children to English schools. This resulted in folding up of Tamil schools rapidly.

But paradoxically, for the Indian community of Tamil ethnicity, Tamil is not just their mother tongue, but a matter of identity to which they are emotionally twined. This milieu, triggered debates, among the Tamil community, on the benefits and losses arising out of the new education policy.

Eminent poet Paranan strongly advocated the bilingualism and pleaded with parents to opt for English education in his poem Iru Vizhigal (“Two eyes”)

Only when our Tamil children

Learn Tamil, the mother tongue

And English, the global tongue

Their future will flourish

Hence

Beloved parents

I plead with you

With folded hands

To let your children

Learn Tamil and English [34]

Interestingly, Irama.Kannabiran, an English teacher by training, speaks out his apprehension on the future of Tamil as a language spoken at home. Classifying Tamil community into three categories, There were debates in Tamil community on the benefits and losses arising out of the new policy -those who speak only Tamil, those who speak only English and those who speak a mix of both the languages- one of his characters in his novella Vazhvu (“life’) expresses its anxiety about the third group. This group, whom the author describes to be in a transitional phase, may opt for a language other than their mother tongue, argues Kannabiran. [35]

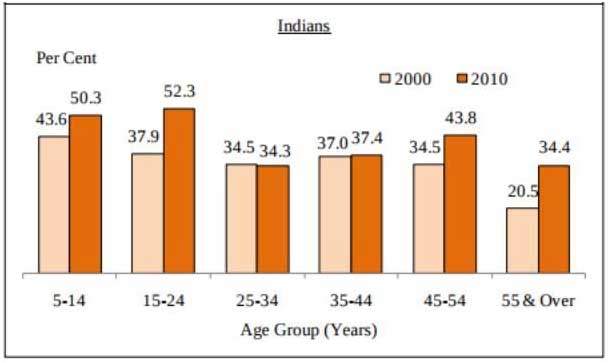

His fears have come true as evidenced by the chart below [36]

Chart 1: Proportion who Spoke English Most Frequently at Home Among Resident Population Aged 5 Years and Over by Ethnic Group and Age Group

“Concurrent with the rise in the level of English literacy, the usage of English at

home became more prevalent.Correspondingly, the use of Malay and Tamil

as home language was less prevalent among the Malays and Indians respectively in

2010 compared to 2000” observes Census report 2010 [37]

b)Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE)

Though PSLE was launched long before independence (The first PSLE was held from 2 to 4 November 1960) [38] it acquired new dimensions since 1992. Under a new system, based on the proposals made by a review committee tasked to improve Singapore’s education system, opportunities for students to get into ‘good’ secondary schools were determined on the basis of their Aggregate T-Scores. Aggregate T-Score indicates how well a student has performed on average in all four subjects relative to his/her peers and is used specifically for the purpose of determining the priority of admission to secondary schools [39]

In the competitive environment of Singapore, where the dictum of meritocracy prevails, this has caused a state of anxiety more among the parents than students.They pressure children, at least a year ahead, to devote more attention to studies. Children are barred from playing games and from indulging in all other past times. Their TV time is robbed by tuition classes and weekly holidays are filled with enrichment programs.

Portraying the stress of children through their own words, in her short story six five, Azhagunila, captures the anxiety of the parents as well [40]

Mom has banned me from computer games, cartoons, PSP and soccer – all

with the same excuse of Primary Five! Primary Six! On days without school,

dad used to go out with me and Rahul. Now he doesn’t bring me anywhere.

The numbers five and six make me feel sick. I’d love it if someone could tell

me the secret to join secondary school without having to sit for the PSLE.

On 13 July 2016, Ministry of Education has officially announced the latest revision to the PSLE Scoring System. The aggregate score for the PSLE will be replaced with wider scoring bands from 2021.[41] Yet debates on PSLE are not likely to cease in near future

Status of women

Another area where the transformation in the last fifty years since independence is distinct is the status of Singapore women. In the United Nation’s Human Development Index for 2014 (released in 2015) Singapore is ranked 13 (out of 155 countries) making it the top Asian country for gender equality. [42] Modern Singapore women, unlike the most mothers of 1960s who stayed at home, have access to education and employment at par with men. The employment rate for women is at one of its highest levels – 76 percent for the prime working ages of 25 to 54.

While labour force participation rate (LPRF) for men has almost stagnated at about 76.2 percent for a decade, LPRH for women rose to 60.4 percent in 2016 from 54.3 percent in 2006 [43]

Singapore Census report 2010 reveals another startling information. Girls outnumber boys at higher education as could be seen from the table below

Table 1: Level of education attending Gender wise

| Level of education attending | Male | Female |

| Professional Qualification | 6533 | 8352 |

| University | 31144 | 39242 |

Source: Census of Population 2010 /Singapore Department of Statistics (2010)

Education brings awareness and becoming aware is the beginning of change. With the level of education rising up and the presence in the workforce becoming bigger, women assert themselves in their new roles as career woman. They shun the traditional role of homemaker. This seems to have caused some strains in the man-woman relationship, as could be seen from the following facts:

- Marriages are deferred

- Increased persons preferring singlehood

- Increase in divorces

Deferring marriages or postponing them beyond the age of 25 is a growing trend among the Indian community in Singapore. In the 1980s, more than 50 percent of girls below the age 20, entered into matrimony.In 2015 it was hardly one percent. Currently, more than 50 percent of women prefer marriage after the age of 30

Table 2: Age of women at the time of Marriage (in percentage) [44]

| AGE / YEAR | 1980 | 1990 | 2015 |

| Below Age 20 | 52.9 | 35.9 | 0.90 |

| Age 20-24 | 35.1 | 40.4 | 16.83 |

| Age 25-29 | 9.7 | 18.3 | 45.50 |

| Age 30-34 | 1.6 | 3.9 | 36.58 |

| After age 35 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 17.92 |

2015 figures are based on Statistics on marriages and divorces 2015 [45]

Census report findings confirm this trend. “The proportion of singles among the resident population rose from 30 percent in 2000 to 32 percent in 2010. This reflected the postponement in marriages and a greater tendency for individuals to remain unmarried” says the report. [46]

Census report cited above further observes,” The increase in the proportion of singles between 2000 and 2010 was more prominent for the younger age groups. Among Singapore citizens aged 30-34 years, the proportion of singles rose significantly from 33 per cent to 43 per cent for the males, and from 22 per cent to 31 per cent for the females”[47]

On one hand, marriages are postponed, and on the other divorces are increasing.” The proportion who were either divorced or separated increased from 2.5 percent in 2000 to 3.3 percent in 2010.” says the Census Report 2010[48]

Writers, as conscious keepers for the community, transcends beyond the numbers and seek the answers. Many of them are of opinion that the institution of marriage deny the self-esteem, identity and freedom for women

Elangovan, a SEA Write Award winner illustrate this opinion through a tale, told by a father to his daughter Nisha, in his play, Talaq (“Divorce”)

There was a beautiful salt doll. It did not know what it was. So it journeyed for thousands of miles over land until finally came to the sea. It was fascinated by this strange moving mass, quite unlike anything it had ever seen before. It had kept watching the huge waves.

Hey, who are you? Said the salt doll to the sea

The sea smilingly replied, come and see. You will find out. So the doll waded into the sea bravely. The farther it walked into the sea the more it dissolved, until there was only the mouth of it left. Before that bit was dissolved, the salt doll smiled peacefully and exclaimed in wonder, ‘Now I know what I am”. It disappeared without a name among the waves as a wave.

Nisha you are like that salt doll. The bridegroom who has come from Singapore to marry you is the sea. Henceforth, he is everything to you. [49]

In Amaipu (“System”) a short story by Naa.Govindasamy, another SEA Write Award winner, the protagonist woman character expresses her anguish through these words:

I believe woman loses her individuality and freedom when she enters into wedlock with a man. In this male-dominated society, women are being used as an object of pleasure for many centuries. Men have used women for their selfish ends The marriage laws that are in vogue, are also drafted keeping men’s interest. Woman will not be emancipated unless the system changes [50]

Se.Ve.Shanmugam, a pioneer featured in the gallery of Singapore Literary Pioneers at National Library, gives a piece of advice to woman not to rely on anyone other than themselves if they seek to live in honour and freedom and to think twice before getting into matrimony [51]

It may of interest to know that all these works were written in the late 1980s and early 1990s when the women were trying to assert themselves in marriage. When they failed in their efforts to secure their respect and freedom they opt to quit the marriage, even if it means raising their child single handed. Stories of single parenting are not common, yet it is not rare. Suriya Rethnna, a recipient of Young Writers’ Fellowship by Mont Blanc, and Karikalan award of Tamil University, (Thanjavur, India) describes in a moving story, Iraivanin Kuzhanthai (God’s own child) the pride and plight experienced by a single mother [52]

In an award-winning story, Kolangal (“designs”) Seethalakshmi, brings out the flip side of divorce, the loneliness of a man, in search of a soul mate after two divorces. The story takes a unique angle of a father seeking the permission from an adolescent son, for remarriage, reinforces the inevitable role of family and the unavoidable divorce, a paradox of modern society [53]

Shaanavas, whose short story collection, Moontravathu kai (“Third arm”) won Singapore Literary Prize in 2014, believes, lack of understanding, more than lack of love, is the cause for failure of marriages, (and for any relationship for that matter) in his story Pesa Mozhi (“unspoken language”)[54]

Singapore writers, whether they belong to Gen-X or Gen –Y, male or female, have voiced unequivocally their opinions that are liberal in nature, on marriage, singlehood and man-woman relationship.

Economic Prosperity and Slow down

Singapore’s economic growth over the last fifty years is, as acknowledged worldwide, as unmatched and astounding.

In 1965, Singapore’s nominal GDP per capita was around US$500 which was at the same level as Mexico and South Africa.

In 1990, GDP per capita had risen to about US$13,000, surpassing South Korea, Israel, and Portugal.

In 2015, GDP per capita was about US$56,000. We had caught up with Germany and the United States. [55]

This journey of $500 to $ 56000, a journey which Lee Kuan Yew called ‘from the Third world to the First world’ has brought in prosperity in every Singaporean life, and Tamil community is no exception. Children of workers once engaged in menial jobs like coolies at the dock, scavengers, peons have now socially progressed as doctors, lawyers, teachers and successful entrepreneurs Many have written stories hinting this social change. Pon.Sundarasau’s story “Ippadiyum oru Pizhaippu” (“ a livelihood of a kind”) in his short story collection Ennathan Seyvathu (what to do?) is a story of this kind [56]

Singapore’s economic history endorses the popular American belief that ‘Dependency is death to initiative, and risk-taking is a gateway to opportunity’ Two strategic decisions, made soon after independence, considered unconventional in economic wisdom, at that time, paid off handsomely. They are 1) to shift away from import-substitution in favour of export-led industrialisation and 2) to attract global multinational corporations as vehicles to achieve industrial growth.

But the Singapore story is not without twists and turns. Between 1974 and 2008 Singapore economy was buffeted by one crisis after another:

1974: International oil crisis

1985: Singapore Economic Recession

1998: Asian Financial Crisis

2001: the collapse of the global IT industry

2003: the spread of the deadly SARS virus

2008: the Global Financial Crisis

Among these 1985 recession seems irrational because Singapore’s domestic economy contracted while the global economy was still growing.

Despite the reasons and justifications, this recession pinched the common man, and for some, it was a deadly blow. P.Krishnan, a SEA Write Award winner depicts the plight of a middle-class worker who opts to invest his CPF savings in share market. All of a sudden the stock market crashes and the worker loses not just his money but also his life.[57] Though the author has taken a conservative standpoint in his story, the harsh truth on the vicissitudes of market driven economy remain unassailable

SARS

The outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in February 2003, besides impacting the economy, unleashed a sense of fear among the residents of Singapore. The paranoia was more about those who are alive rather than on the dead. Ironically, hospital staff, who were saving those infected from death, risking their own life, bore the brunt. They were shunned in public places, fearing they may be the carrier of the virus. Cabbies refused to give them a ride, neighbours suddenly turned indifferent and unfriendly, and in some extreme cases, the tenants were asked to vacate, against law.

In a story, They were shunned for treating Sars patients, published by The Straits Times, in 2013, after a decade of the outbreak, Rose Herdawati, Siva Sevakame, and Vasanthi Palanivelu,3 staffs of Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH), recounted their experiences during the outbreak of SARS:

“Whenever the train reached Novena, it would become passenger- free,” remembered Ms Sevakame. “We would take showers and change before going back, but somehow they’d know we were nurses and start moving away. “So I didn’t have to worry about not getting a place to sit,” she added with a laugh… The prejudice was not just from strangers, but from neighbours and family too. MS Herdawati remembered how neighbours who used to exchange cooked food with her mother stopped doing so. Ms Sevakame was then renting a room in a Yishun flat that, with her husband, they shared with her landlady and the landlady’s three teenage children. When her landlady got the wind that Ms Sevakame might have contracted Sars, she tried to evict the couple”. [58]

Interestingly, Jayanthi Sankar captured almost every one of these incidents – shunning by neighbours, neglect by the public, and eviction threat- in a story she wrote in 2003 itself. Titled Mukhangal (“faces”) The story stands as a testimony to the human behaviour in the event of a life-threatening epidemic

Conclusion:

Though the initial inspiration of Singapore Tamil writing originates from Tamilnadu, India, and many of the authors have modelled their style similar to a few of the pioneers of Tamil writing in India, Singapore Tamil writing, is far different from Indian writing, as the milieu in both the countries is very different. Indian writing has a long history and was nurtured by mainstream media to begin with and later through the competition with the little magazines. In contrast, publishing opportunities for Singapore Tamil writing was very limited and hardly there is any room for avant-garde writing or for experimental work. Pioneers who piloted the literary moments in India had greater exposure to European and Russian literature and to works from Latin America. This enabled them to root their works with well-tailored forms and different genre. The pioneers of Singapore writing were deprived of such exposure and took up to writing out of the passion for language and literature despite not being materially rich. They were motivated by the social movements rather than by literary movements.

Hence it would be ridiculous to compare the Tamil writing from both the places in terms of standards or craft. It would be equally goofy if Singapore writers ape the Indian Tamil writers.

I commenced my study on the Singapore Tamil writing with this clarity and with the firm resolute that I will not make any qualitative assessment of the works of Singapore writers as it is out of the purview of my study. My focus was on how they have voiced the social transformation and I studied their text and its context

I find Singapore Tamil writers have been responding to the various changes that had taken place in the last half-a- century, at their best, though not with great articulation. They have voiced their concerns, anxiety and happiness that were brought into their lives by the social and economic transformations within a narrow framework of their home or neighbourhood. Political discourses are rare. Hardly have they initiated any literary movements through their works.

Without any reluctance I would say, Singapore Tamil writing has been echoing the voices of the community that are sometimes poignant, sometimes bemused, and most of the time moderated.

References:

- 1.Muhammed Abdul Kadir, Pulavar, (1872) முனாஜாத்துத் திரட்டு (Munajattut tirattu) Singapore: J. Paton Government Printer Retrieved from Book SG http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/5f39c786-6019-47c7-895d-ee3e855f5257.a

- [Advertisement] (1876, February 29) Straits Observer (p.2) Microfilm NL2212

- 3.Irama.Kannapiran (2011) சிறுகதை (1887-1965) (“Short story 1887-1965”) in சிங்கப்பூர் தமிழ் இலக்கிய வரலாறு ஓர் அறிமுகம் ( History of Singapore Tamil Literature An Introduction ) (p 129) Singapore: Association of Singapore Tamil Writers

- Dr.Tan Tin Wee (2011) Naa Govindasamy, Tamil Computing and Tamil Internet: Quest for Globalisation of Tamil IT in Na.Govindasamy, A Creator Singapore National Library Board (p.28)

- National Library Board and National Archives of Singapore. (2007).Singapore The First Ten Years of Independence 1965 to 1975,( p.6) Singapore. Call no. English 959.5705 SIN -[HIS]

- Ibid.p17

- Veeramani.A ( 2004) in Chitra Saṅkaran̲ ; Sp. Thiṇṇappan̲.(Ed) முதல் படி அனைத்துலக அரங்கில் தமிழ், (Tamil in an international arena, first step) /. Singapore : UniPress,

- Tamil Murasu 10 August 1965 Microfilm NL4379

- பிரிந்தாலும் சகோதரர்களே (“Brothers even if we part”) Tamil Malar 11August 1965 Microfilm NL4363

- Perumal.K (1979) சிங்கப்பூர் பாடல்கள் (“Hymns on Singapore”) Singapore: Maraimalai Publications. Retrieved from Book SG: http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/81bb08d4-4a17-4a4c-a657-4a0abc3c54aa.aspx

- Ibid

- Paranan (1985) தோணி (“Boat”) Singapore : Tamil̲vaḷarccip Paṇṇai, Retrieved from Book SG. http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/5f7b57b5-5896-4622-af3c-b2ca5518788b.aspx

- Palanivelu.Na.(2013) கடமை (“Duty”) in Sundari Balasubramaniam (ed) A Selection of Na.Palanivelu’s Poems.(p.33) Singapore: National Library Board

- Aandeappan.Naa. (2014) உயர்தர வைரம் (“Classy Diamond”) in மீசை முளைக்காத காதல் (“adolescent love”)(p.43) Singapore: Baraniya Pathipagam Retrieved from Book SG. http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/24e3623b-9545-4f08-847c-a7576169cd3c.aspx

- Elango Pichinikkadu (2017) ஆகஸ்டு ஒன்பது (August 9) in அங்குசம் காணா யானை (“elephant without elephant goad’) (p.29) Singapore: Author

- National Library Board and National Archives of Singapore. (2007).Singapore The First Ten Years of Independence 1965 to 1975,( p.198) Singapore. Call no. English 959.5705 SIN -[HIS]

- ஒன்பதாண்டுகளில் ஒன்றரை லட்சம் பேர் மறுகுடியமைப்புச் செய்யப்பட்டனர் [“Under Singapore’s Urban Renewal Programme some 150,000 people have been resettled over the last 9 years”] (1969 January 25) Tamil Malar,(p.9) Microfilm NL 5835

- Kumarasamy.C, (1980). பாசிர் பாஞ்சாங் வட்டாரத்தில் வாழ்க்கை [ “Life in Pasir Panjong”] in கடந்த இருபத்தைந்து ஆண்டுகள் [“Last Twenty Five Years”] (p.67 ) Singapore Indian Cultural Programme Sub-committee, 25th Anniversary Celebrations Call no.: Tamil 959.5705 KAD

- Elangkannan.Ma, (2006) நினைவுகளின் கோலங்கள் (designs of memories) p.140 Chennai, Chuvadi. Retrieved from Book SG. http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/0ae587fe-2ae1-4f57-b183-edaccce88935.aspx

- Kanagalatha (2007) வீடு (“Home”) In நான் கொலை செய்யும் பெண்கள் ( “The women I kill”) (p.93) Singapore . Retrieved from Book SG, http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/bc631436-b581-4db6-862a-8b1fbafd33d5.aspx

- Ma. Elangkannan, (2006) நினைவுகளின் கோலங்கள் (“designs of memories”) (p.172) Chennai, India: Chuvadi. Retrieved from Book SG. http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/0ae587fe-2ae1-4f57-b183-edaccce88935.aspx

- Palanivelu.Na.(1997) சிங்கையின் பொருள் வளம் (“Prosperity of Singapore”) in கவிஞர் ந. பழநிவேலுவின் படைப்புக் களஞ்சியம். Vol. II (“Collected works of Na.Palinivelu Vol.II”) (p.219) retrieved from Books SG http://eservice.nlb.gov.sg/data2/BookSG/publish/c/c731e365-2b8a-42d3-a306-aad1ee9a4097/web/html5/index.html?opf=tablet/BOOKSG.xml&launchlogo=tablet/BOOKSG_BrandingLogo_.png&pn=231

- Iqbal. K.T. M (1975) எங்கள் நாடு (Our Country) in இதய மலர்கள் (“flowers from heart”) (p.36) Kadayanallur, India:Panimalar Publications Retrieved from Book SG. http://eservice.nlb.gov.sg/data2/BookSG/publish/4/411236d6-bd71-408f-94eb-57970d288529/web/html5/index.html?opf=tablet/BOOKSG.xml&launchlogo=tablet/BOOKSG_BrandingLogo_.png&pn=1

- Paranan (1985) இசை நட்டு வாழ்க (“Long live with glory”) in தோணி (“Boat”) (p.69) ”) Singapore : Tamil̲vaḷarccip Paṇṇai, Retrieved from Book SG. http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/5f7b57b5-5896-4622-af3c-b2ca5518788b.aspx

- Puthumaithasan (2000) அடுக்கு வீட்டு அண்ணாசாமி (“Annasami and his apartment”) ( p.7) Retrieved from Book SG http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/89a1ae62-55e5-4ccb-ab6c-91d8ad68b1f6.aspx

- Bukit Panjong Citizen’s Consultative Committee (2016) Bukit Panjang : from kampong to town, p.112 Singapore: Call no.: English 711.4095957 BUK

- Noorjahan Sulaiman (2012) வேர்கள் (“Roots”) (p.64) Singapore: Goldfish Publication

- National Library Board and National Archives of Singapore. (2007).Singapore The First Ten Years of Independence 1965 to 1975,( p.84) Singapore. Call no. English 959.5705 SIN -[HIS]

- Citizen Soldiers (1967, September11) The Mirror (p.1, 4-5)

- National Library Board and National Archives of Singapore. (2007).Singapore The First Ten Years of Independence 1965 to 1975,( p.82) Singapore. Call no. English 959.5705 SIN -[HIS]

- Kannapiran,Irama. (2015) தானா மேரா டைரி (“Tanah Merah Diary”) in Ira.Durai Manikam, Irama. Vairavan et.al (ed) சிங்கப்பூர் பொன்விழாச் சிறுகதைகள் (Golden Jubilee short-stories) (p.80) Singapore : Association of Singapore Tamil writers

- Shanmugam, Se.Ve. (1983) இராம. கண்ணபிரான் -ஒரு கண்ணோட்டம் (“ A review on Irama.Kannapiran” in சிங்கப்பூரில் தமிழும் தமிழிலக்கியமும்-4 (“Tamil Language and Tamil Literature in Singapore”) Conference Proceedings of University of Singapore Tamil Language society -1983

- Kumarasamy.C, (1980). பாசிர் பாஞ்சாங் வட்டாரத்தில் வாழ்க்கை [ “Life in Pasir Panjong”] in கடந்த இருபத்தைந்து ஆண்டுகள் [“Last Twenty Five Years”] (p.67 ) Singapore Indian Cultural Programme Sub-committee, 25th Anniversary Celebrations Call no.: Tamil 959.5705 KAD

- Paranan (1982) இரு விழிகள் (“Two eyes”) in எதிரொலி (“Echo”) (P.43-44) Singapore: Tamil Valarchi Pannai Retrieved from Book SG : http://eservice.nlb.gov.sg/data2/BookSG/publish/0/0c5ca4b1-5a0d-4082-870e-526c0c1120df/web/html5/index.html?opf=tablet/BOOKSG.xml&launchlogo=tablet/BOOKSG_BrandingLogo_.png&pn=1

- Kannabiran (2015) வாழ்வு (“Life”) (p.31) Singapore: Crimson Earth

- Singapore Department of Statistics (2010) Census of Population 2010 Statistical Release 1 Demographic Characteristics, Education, Language and Religion (p.27)

- 37. Ibid (p.25)

- 38. Primary school exams for 4 streams. (1960, May 20). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- 39. Singapore Examinations and Assessment Board, retrieved from its website http://www.ifaq.gov.sg/SEAB/apps/fcd_faqmain.aspx?qst=hRhkP9BzcBImsx2TBbssMsxu7lqt6UJK70a1wAEVmyfdSZlp3kC3qEU1uwdD2zxBC8h26bwjs%2FIwvamUXpJQllIbGr3zfx%2Fg6R5G3kQwdaBqrmc6VVtGVreSd34s3fzQd2XjpEaXHjFH9k4Aky4ad22Tv9ZVP3e82AhV2YIeMwaGIBKFIrvh5zfUcyEdjkBGvw8b%2Bh1woqMmu1%2FCwl6UK4xSGccfs%2FuC2rGMLPsW7lE%3D#FAQ_93280

- 40. Azhagunila, (2015) ஆறஞ்சு (“Six five”) (p 40-41) Singapore: Author

- 41. Ministry of Education retrieved from their website https://www.moe.gov.sg/microsites/psle/

42. Singapore is top Asian nation for gender equality: UN report (December 29, 2015) The Straits Times. Retrieved from SPH website : http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/singapore-is-top-asian-nation-for-gender-equality-un-report

- Growing number of women in the work force ( March 13,2017) The Straits Times

- 44. Veeramani.A.(1996) துரித மாற்றம் காணும் சமுதாயங்களில் இளம் பெண்கள் (“Young women in rapidly changing societies”) Singapore: Singapore Tamil Youth’s Club

- Singapore Department of Statistics (2015) Statistics on Marriages and Divorces

- Singapore Department of Statistics (2010) Census of Population 2010 Statistical Release 1 Demographic Characteristics, Education, Language and Religion

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Elangovan (1999) Talaq (Divorce) (p.15-16) Singapore: Author Call no: English S894.8112 ELA

- Govindasamy, Naa.(1991) அமைப்பு (“system”) in தேடி (“in search” ) (p.76-77) Singapore : Orchid Publishing House, 1991. Call no: Tamil S894.811371 GOV

- Shanmugam, Se.Ve. (1989) மற்றொன்று (“another one”) (p.214-225) in Singapore Tamil Sirukathaikal. Chennai India, Tamil Puthakalayam Call no. Tamil

- 894.811371 SIN

- Suriya Rethnna (2013) இறைவனின் குழந்தை (“God’s own child”) in ஒரே வானம் (under one sky) Singapore : National Library Board Call no. Tamil

- 808.831 MAL

- SeethaLakshmi (2001) கோலங்கள் (“designs”) in கண்ணாடி நினைவுகள் (“memories of reading glass) (P 113-122) Singapore: Author retrieved from Book SG http://eservice.nlb.gov.sg/data2/BookSG/publish/5/5c6eaee6-1e49-44af-a3bf-cba090284419/web/html5/index.html?opf=tablet/BOOKSG.xml&launchlogo=tablet/BOOKSG_BrandingLogo_.png&pn=3

- Shaanavas (2013) பேசாமொழி in மூன்றாவது கை (“Third arm”) (p 78-84) Chennai, India: Thamizhvanam . Retrieved from Book SG: http://eservice.nlb.gov.sg/data2/BookSG/publish/c/c1791a86-87f8-43a3-b27f-99663629f589/web/html5/index.html?opf=tablet/BOOKSG.xml&launchlogo=tablet/BOOKSG_BrandingLogo_.png&pn=1

- Ravi Menon (2015) Keynote address at Singapore Economic Review Conference 2015 on 5 August 2015 Retrieved from the website of Monetary Authority of Singapore: http://www.mas.gov.sg/News-and-Publications/Speeches-and-Monetary-Policy-Statements/Speeches/2015/An-Economic-History-of-Singapore.aspx

- Sundararasu,Pon. (1981) இப்படியும் ஒரு பிழைப்பு ((“ a livelihood of a kind”) (p.64-75) in என்னதான் செய்வது? (What to do?)Chennai, India: Tamil Puthakalayam. Retrieved from Book SG: http://eservice.nlb.gov.sg/data2/BookSG/publish/3/3219e902-92a5-4eba-aec1-4f5fd612ad42/web/html5/index.html?opf=tablet/BOOKSG.xml&launchlogo=tablet/BOOKSG_BrandingLogo_.png&pn=1

- Krishnan,P.(1993) ஓய்வு (Retirement) in புதுமைதாசன் கதைகள் (“Stories of Pudumaidasan”) Singapore: Okkid Pathipagam Retrieved from Books SG. http://eservice.nlb.gov.sg/data2/BookSG/publish/e/eaefc1ba-16bd-41c2-b8a5-d9609ecb0dce/web/html5/index.html?opf=tablet/BOOKSG.xml&launchlogo=tablet/BOOKSG_BrandingLogo_.png&pn=1

- They were shunned for treating Sars patients ( 12 February 2013) The Straits Times. Retrieved from the website of Tan Tock Seng Hospital https://www.ttsh.com.sg/about-us/newsroom/news/article.aspx?id=4419

- Sankar, Jayanthi (2013) முகங்கள் (“Faces”) in ஜெயந்தி சங்கர் கதைகள் (Jayanthi Sankar Kathaigal) Chennai India, Kavya

For Further Reading :

Books on line (Books SG):

- Sali,J.M. அந்த நாள் : சிங்கப்பூர் சிறுகதைகள் (That Day: Short stories on Singapore http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/0e25916a-914e-4cf3-ad39-b496e86b3d92.aspx

- Ilango, Pichinikadu: இரவின் நரையில் : (Night’s grey)

http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/18a3c9ed-6e20-4458-a300-3d3fdb76ff8b.aspx

- Ikkuvanam.V. இன்பநலக் காடு (Forest of Pleasure) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/496ad19f-df68-408f-9b0f-8de21d6bd862.aspx

- Varadarajan, A.K. ஐம்பதுக்கு ஐம்பது (SG50) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/1243b79a-f89b-4d2b-af4e-b6f5aa252972.aspx

- Ilangkannan .M. குருவிக் கோட்டம் (Bird Sanctum) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/d8259ae0-c354-4c8f-a012-48fa0a6db192.aspx

- Anbalagan ,M. (ed) கூடி வாழ்த்தும் குயில்கள் : சிங்கப்பூர் தேசியதினக் கவிதைகள் (Anthology of Poems on National Day) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/3f61cb82-a3a5-4a50-842b-b940ffd16262.aspx

- Ulaganathan. I சிங்கப்பூர் சிறப்பதிகாரம் ( Poems on Singapore Politics and government) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/764ceeab-a983-4f3e-88ec-1061ecb1fbf6.aspx

- Sivakumaran., A.R. சிங்கப்பூர் மரபுக் கவிதைகள் : ஒரு திறனாய்வு (Criticism on Singapore Verses) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/113a7dc8-edbd-4b8c-a34a-b641538b0f2b.aspx

- Veeramani.A. சிங்கப்பூர் வளர்ச்சியில் தமிழ் மொழி (Tamil in the development of Singapore) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/6748b9b5-c1b8-493c-9d5d-30922bee4d0f.aspx

- Thinnappan,Suba. சிங்கப்பூர்த் தமிழ் இலக்கிய வரலாறு ஒரு கண்ணோட்டம்(An overview of Singapore Tamil Literature) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/a5f87369-39b6-41d9-8d73-c30fb6993ef9.aspx

- Thinappan.Suba சிங்கப்பூரில் தமிழ் : மொழியும் இலக்கியமும் (Tamil Language and Literatrure in Singapore) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/5fdcdfcf-8319-4ca2-9942-4d19329e300a.aspx

- Aravindan,Kamaladevi. சூரிய கிரஹணத் தெரு (Street eclipsed with sun) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/91b35b19-7e24-4577-ac25-e9d759341c99.aspx

- Latha. தீ வெளி (Fiery Space) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/da9bc286-17c1-406c-9b6d-ab54fa07a176.aspx

- Napoleon நானும் என் கருப்புக்குதிரையும் (Me and my black horse) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/cd92e639-29a4-44ef-adfb-7a5f794eeb54.aspx

- Aravindan Kamaladevi. நுவல் (speak) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/406e523d-ad56-4ba4-8ade-b66fec2b04e3.aspx

- Latha. பாம்புக்காட்டில் ஒரு தாழை (In the snake forest) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/db1eb242-4517-4d99-9067-51b0b7f56d99.aspx

- Indrajith புதிதாக இரண்டு முகங்கள் (Two faces that are new) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/73982d29-db6a-4f41-8ee4-b97db59547de.aspx

- Noorjahan Sulaiman பொழுது புலருமா? (Will there be dawn?) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/f65955d9-27c9-421b-a31b-061e983b48ae.aspx

- Kumar,M.K. மருதம் (Marudam) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/e9ed1110-9aa4-44f6-81dc-acbe45501cc4.aspx

- Association of Singapore Tamil Writers மாமனிதருக்குப் புகழாரம், லீ குவான் இயூ 90 (A tribute to the great man Lee Kuan Yew 90) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/24e3623b-9545-4f08-847c-a7576169cd3c.aspx

- Indrajit வீட்டுக்கு வந்தார் (He came home) http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/detail/951cf56a-c443-451f-a61d-aa40e066959d.aspx

Books (Print)

- Gopinathan.S Singapore chronicles: education Institutte of Policy Studies Singapore Call no. 370.95957 GOP

- Seetha Lakshmi (ed) சிங்கப்பூரில் கல்விக் கொள்கையும் நடைமுறையும் Call no.Tamil 370.95957 GOP

- Association of Singapore Tamil Writers: History of Singapore Tamil Literature: An introduction 1872-2010 Call no. Tamil 894.81109 SIN

- Bala Baskaran: கோ.சாரங்கபாணியும் தமிழ்முரசும் Call no: Tamil 070.4092 BAL

- Srilakshmi.M.S. : சிங்கப்பூர் தமிழ் இலக்கியம் ஆழமும் அகலமும் Call no. Tamil 894.811109 SRI

- Palu Manimaran (Ed) வேறொரு மனவெளி Call no. TamilS894.811372 VER

- Kumar M.K. நதிமிசை நகரும் கூழாங்கற்கள் Call no: Tamil S894.811172 NAT

- Madahangi. பெரிதினும் பெரிது கேள் Call no. Tamil 894.8113 MAD

- Ponraj Sidduraj: மாறிலிகள் Call no: Tamil S894.811372 SIT